The tradition of Halloween changed forever during WWII.

Halloween, as with so much of America, was transformed by WWII. Before the most significant conflict in human history, the annual tradition was widely viewed as an annoyance —an all-too-predictable disturbance —marked by widespread vandalism: smashed Jack O’Lanterns, broken white fences, teenage rambunctiousness.

There were no pumpkin-flavored lattes, nor crowds of overweight children armed with orange buckets made in China, on the hunt for a lifetime’s supply of Reese’s peanut butter cups. Before WWII, Halloween was more about trickery and rebellion, not renting Batman costumes. It was a real nuisance, not mass-marketed entertainment. If you didn’t give out candy before Pearl Harbor was attacked, you might actually get tricked.

It has always been somewhat ironic that in such a religious country, Halloween has been so popular. It dates back some two millennia, originating with the Celts’ holiday of Samhain, which marked their new year. The worlds of the living and dead merged. Demons roamed. Bonfires roared as the Celts dressed up as the dead, disguising themselves as the demons they wanted to avoid. With the influx of Irish and Scottish immigrants to America came many Celtic traditions, including Halloween.

The first WWII Halloween in the US arrived in 1942, when victory was far from assured. Millions of Americans were in service or working long shifts in factories, and more and more youngsters escaped adult supervision. The puritan streak, ever present in American public life, quickly came to the fore with much hand-wringing about idle youth and the inevitable delinquency that would result from too many kids with too much time on their hands.

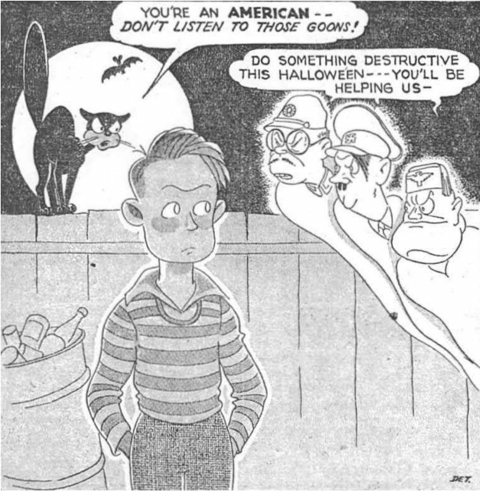

There was also a broader, general paranoia about social breakdown brought on by the tensions of war. Halloween was a national security threat, it seemed, and should be banned —or at least tightly controlled and rationed. Left to their own devices, young Americans not yet called to the killing fields of Europe and the Pacific might turn into the savages their absent brothers and fathers were trying to defeat.

Many communities across America actually canceled Halloween in 1942. Curfews were imposed to deter pranksters. The Des Moines Register went so far as to compare high-spirited youngsters to saboteurs, an adolescent Fifth Column “helping the Axis.”

An article that appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, headlined “Halloween Pranksters Aid Foe,” echoed the sentiments of many other party-poopers: “Uncle Sam sorrowfully warned his juvenile nieces and nephews that the only way they could go hobnob with the hobgoblins this All Hallow’s Eve was to stay at home and make faces at each other.” Ringing doorbells and then running away was tantamount to treason – Rosie the Riveter needed her beauty sleep before starting her next 12-hour shift in a munitions factory, or on a production line churning out B-17 bombers and Sherman tanks at an astonishing rate.

Thankfully, wiser and fun-tolerating forces prevailed. Instead of banning Halloween, some towns organized costume parties and dances to draw would-be troublemakers off the streets. Besides, thanks to the strict rationing of sugar, searching for candy was pointless. Magazines intervened, providing ration-friendly recipes for spiced cookies and donuts. Less nourishing was the Southern tradition of listing separate activities for black and white children in newspapers. The US military was still segregated, and so too was much of America, although women and minorities were serving in combat zones. It would be several more decades before wearing blackface to a Halloween party would become verboten in white suburbs.

Children all across America dressed up in new costumes, pretending to be Red Cross nurses or Uncle Sam. But not all young Americans behaved themselves now that a global war raged. One newspaper in Louisiana reported that, despite exhortations to be virtuous, pranksters were still at large, “soaping windows, turning over garbage cans, taking chairs and benches and other things left out in the open. There were some cases of actual vandalism reported, such as things being taken or broken.”

You don’t change customs and behavior overnight, but the official parties and other organized events were a huge success, and vandalism declined markedly in 1942. By war’s end, the culture of Halloween was forever changed. With the mushrooming of suburbia in the 1950s, providing ideal routes through neat neighborhoods with sidewalks, and with the advent of pre-packaged goodies, trick-or-treating surged in popularity, and Halloween became ever more “safe and sane” and child-centric. Eighty years after WWII ended, the tricks have all but disappeared in a vast cascade of bite-sized candy.