85 years ago, an American daredevil helped save the free world.

The first World War II movie I watched as a kid in dull, 1970s England was The Battle of Britain. The first Airfix model I assembled was a Spitfire – it hung from a thread along with a Mosquito and Lancaster above my desk as I read countless action comics about tough, young Brits who defeated Adolf Hitler and his followers.

In the summer of 1940, 85 years ago, World War II had been ongoing for nearly a year. Hitler’s Germany was victorious. The United States remained neutral. As Winston Churchill later noted, it was a time when “the British people held the fort alone till those who hitherto had been half blind were half ready.” However, some Americans chose not to stay on the sidelines.

That summer and fall, a handful of American pilots fought against the Nazis in the Battle of Britain. This remarkable group of rogue flyers included ex-barnstormers, a Minnesota farm boy, and the greatest bobsled champion in American Olympic history. All had defied strict neutrality laws—thereby risking loss of their citizenship and imprisonment if they dared to return home—in order to join what they regarded as the best flying club in the world: Britain’s Royal Air Force.

With only minimal training, these Americans fought against some of the Luftwaffe’s top aces in the greatest one-on-one contest in aviation history, and by October 1940, they had helped save England from a Nazi invasion. Many more Americans soon joined them, enough to form three squadrons—all of this happening many months before Pearl Harbor marked America’s entry into the Second World War.

Among these noble soldiers of fortune, I have a clear favorite. Eugene Tobin was a tall, red-haired, wisecracking 23-year-old during the Battle of Britain, and a diligent diarist. He’d paid for flying lessons in the late 1930s by working as a guide and messenger at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film studio. He was convinced that the war in Europe would come to America sooner or later, and he didn’t want to be drafted into the army as a grunt when it did. He wanted to be a fighter pilot and duke it out against evil in the skies.

Above all, Tobin was looking to fly the “sweetest little ship” in the world, the Supermarine Spitfire, designed by Englishman R. J. Mitchell, first flown in 1936, and capable of over 350 mph, three times faster than any plane he had flown. “I just felt I wanted to fly some of these powerful machines,” Tobin recalled. But only by risking his neck in someone else’s war would he get that chance. The gamble seemed well worth it.

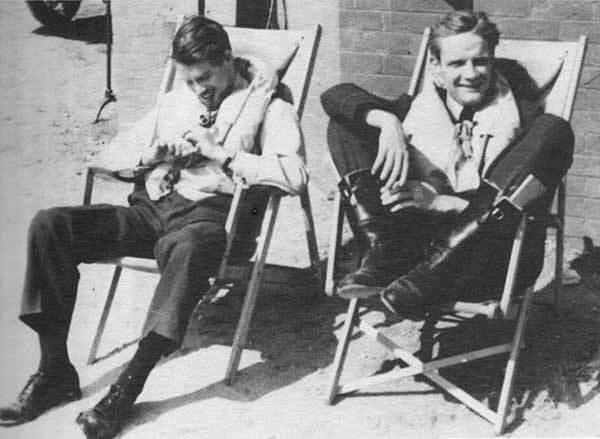

In early July 1940, having crossed the Atlantic and then escaped the Nazis as France fell, Tobin was assigned to 609 Squadron at Middle Wallop airfield in southern England, where he was quickly accepted as an honorary Brit. To the young British pilots, the lanky “Red” Tobin seemed like a cowboy out of a Hollywood movie.

In 2005, I took Tobin’s sister, Helen, to the base where Eugene and 609 had flown from. Remarkably, she was nearly 90 and had traveled alone from Olympia, Washington, to England—to honor her brother. I pulled over the hired car on a busy road and told Helen to look through a gate. About fifty yards away, there was a dispersal hut—a relic from summer 1940, preserved out of respect and nostalgia.

It was from this dilapidated, lonely hut that Tobin and other flyboys would run to their Spitfires—their ships—when they were “scrambled”—called to battle. I showed Helen a photo of her brother sitting outside the hut in August 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain, smiling with maps tucked into his flying boots. She smiled. So near but so far—so close to him as he was in 1940, to the brother she so adored, but several decades too late to hold him, to touch him once more.

I told Helen that on August 20, 1940, Tobin attacked a group of Bf 110 fighters escorting Junkers 88 bombers and badly damaged two of them. Day after day, that late summer, the pilots fighting for Britain engaged in dogfights above England and the Channel, vapor trails crisscrossing the clear blue skies.

On September 15, 1940, over a thousand German planes crossed the Channel toward London, aiming to terrorize the British and deliver a knockout blow to the RAF’s Fighter Command. The battle’s climax arrived as Tobin shot down a Dornier bomber and likely destroyed a Bf 109.

It was a disastrous day for the Luftwaffe. The combined losses to Hitler’s air force were so severe that the usual waves of German fighters did not return the next day. Faced with such intense resistance, Hitler decided to postpone “indefinitely” his planned invasion of England, Operation Sea Lion.

It was not yet clear to Churchill’s fighter boys that they had fought off the greatest threat to Britain’s survival in a thousand years, and had done so by, in Churchill’s words, the “narrowest of margins.”

Four days after the climax of the Battle of Britain—on September 19, 1940— Tobin became one of the first Americans to join the new 71 “Eagle” Squadron, the first all-American unit in RAF history. 71 Squadron first saw active duty on January 4, 1941. Later that year, on September 7, 1941, Red Tobin joined 15 pilots from 71 Squadron in a sweep over northern France. Around 75 miles inland, radar announced the presence of bandits to their rear, between them and the Channel. The bandits turned out to be 100 Bf 109s that had waited for the RAF planes to fly inland.

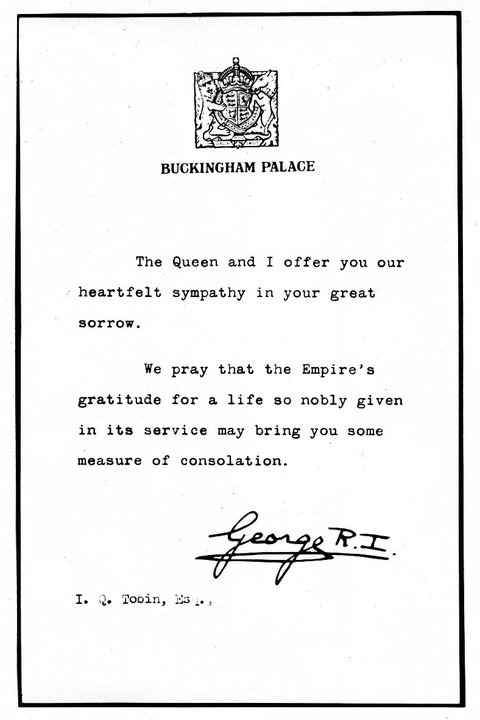

The 109s attacked the Spitfires from above at 29,000 feet, then climbed to higher altitude and attacked again. Two pilots from 71 Squadron were killed, including Tobin, and three had to bail out. Helen told me she could still remember hearing about her brother’s death as if it happened yesterday.

That summer of 2005, I returned to London with Helen, and a few days later, joined her at Westminster Abbey for a commemorative service for The Few – the pilots of the Battle of Britain. Prince Charles—now king—was there with Camilla, along with some Battle of Britain pilots and their families. I was in complete awe of the old men, some dressed in dark blue, who had been my childhood heroes, shaking hands with our future king.

Helen was a bit starstruck but unfazed by protocol, whether she should bow or what to say when addressing Charles. She was much more focused on finding her brother’s name on a new memorial than on upsetting a royal. Later that day, I held her arm as she searched for “Eugene Tobin” on an unveiled memorial on the Embankment by the Thames. She was overjoyed and relieved to see how he had been remembered and honored, a testament to the profound impact his life had on others.

Helen returned to the US and passed away several years later, the fiercely proud sister of an American flyboy who helped save the free world. Today, 85 years after the Battle of Britain, we should remember the debt we owe her brother and his fellow RAF pilots, of whom Churchill famously said: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”