Vassily Grossman’s account of Treblinka is as important and disturbing as ever.

Every year, I approach Holocaust Memorial Day with mixed feelings. Having written about the Holocaust, specifically in a book about the murder of the Hungarian Jews, I welcome any day on which as many people as possible might reflect on the enormity of the crimes committed by the Nazis and their accomplices in Europe during WWII. But I also wonder whether we have learned much, if anything, in a world where anti-Semitism is ever more prevalent, and why ancient hatreds have not yet been defeated.

Here are a few sobering statistics to consider. According to the FBI, anti-Jewish hate crimes reached record levels in the US in 2024. According to the Anti-Defamation League, there were 9,354 antisemitic events in 2024, the highest number the organization has tracked since it started in 1979. Physical attacks rose 21%. The results for 2025 may be even worse.

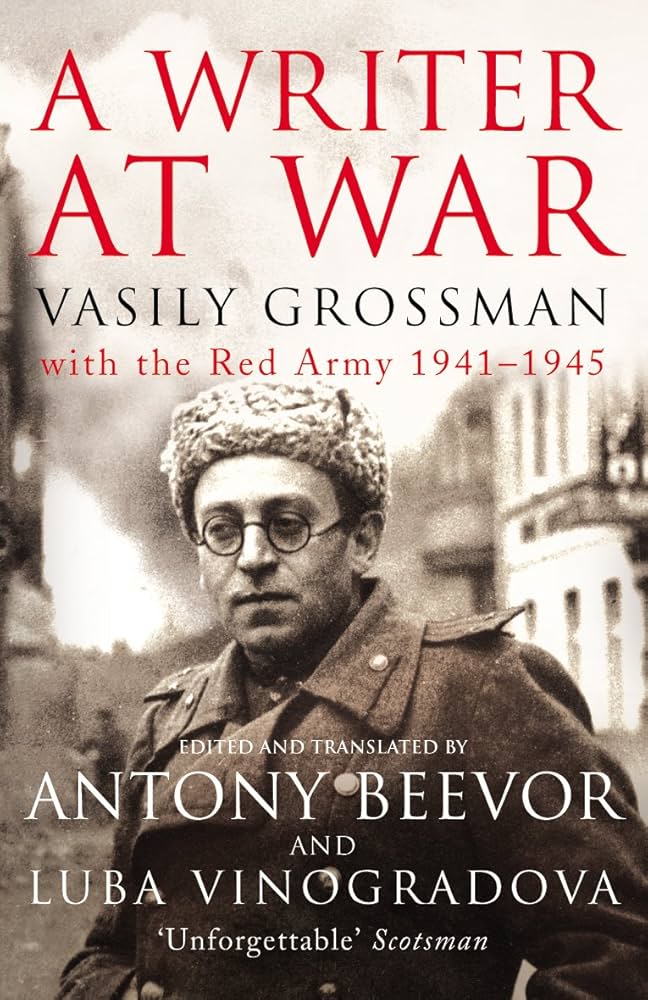

This January 27, Holocaust Memorial Day, marks the 81st anniversary of the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz. Wanting to understand more about that liberation and how liberators on the Eastern Front reacted to the atrocities they found, I picked up a tremendous book, “A Writer At War: Vasilly Grossman with the Red Army, 1941-1945,” a collection of Grossman’s journals and journalism, edited and translated by Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova. As an aside: Beevor’s book, “Stalingrad,” is my favorite WWII history.

A Ukrainian Jew, Grossman became a reporter for Red Star, the Red Army newspaper, in 1941 and covered the war on the Eastern Front until the bitter end. At least eight million members of the Red Army died during the period Grossman reported, often from the frontlines, from the outskirts of Moscow, from the factories of Stalingrad, from the killing fields of Kursk, and in the ruins of Warsaw and, finally, Berlin. By contrast, around 420,000 Americans died during WWII.

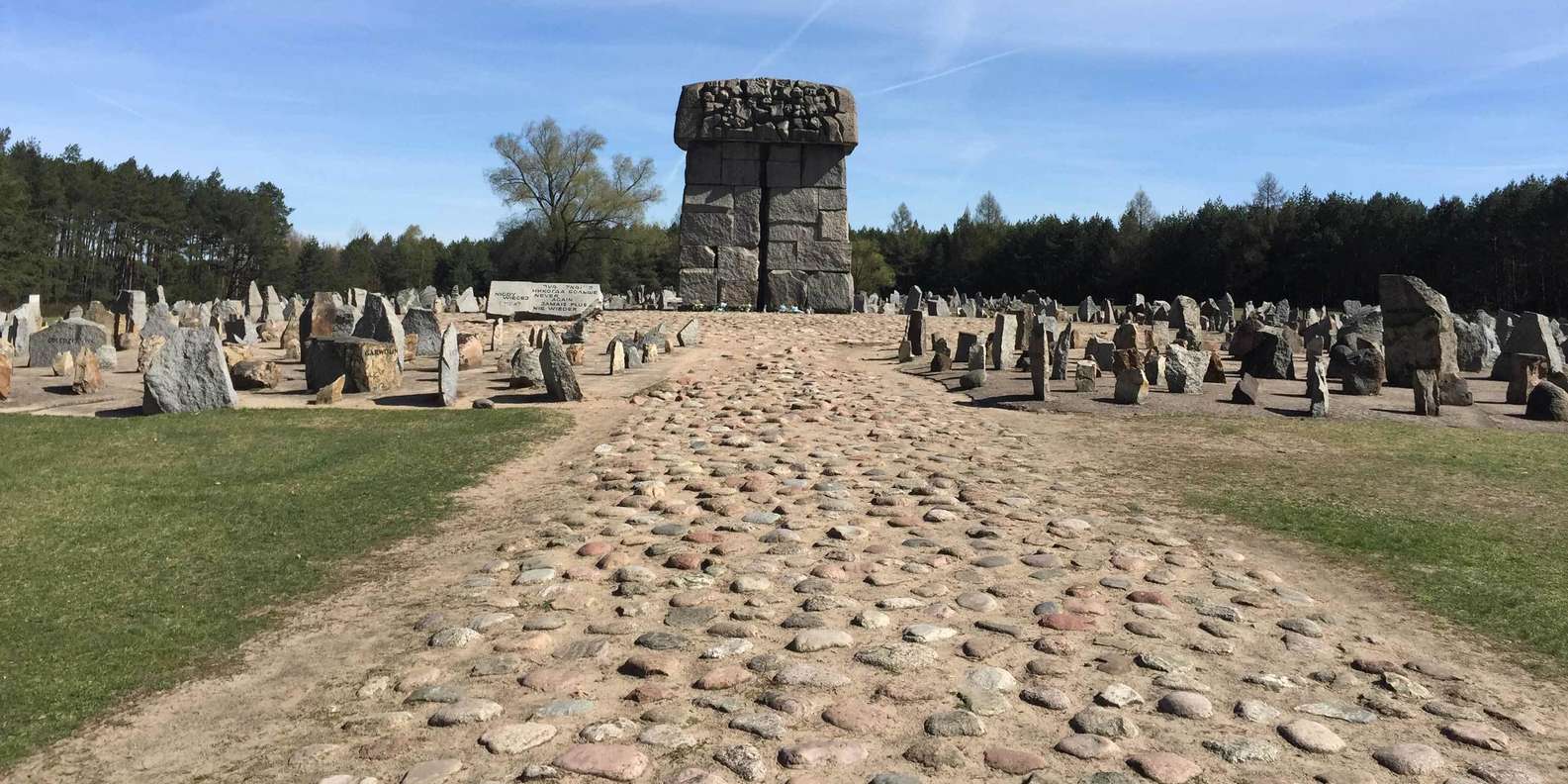

Of the dozens and dozens of visceral reports, one stands out to me and many others. In late July 1944, the Red Army reached the site of Treblinka, an extermination camp, in Poland. The SS had tried to destroy any trace of the camp where at least 800,000 people had been killed, he reported, by just 25 SS men and a hundred or so Ukrainians. Even so, Grossman managed to interview some of the forty-odd survivors found by the Red Army and local Poles. The report, titled “The Hell of Treblinka”, made for devastating reading, and still does.

Under Himmler’s orders, the SS tried to obliterate any trace of their crimes, arguably without parallel in the long history of genocide. Treblinka was razed and burned. When Grossman visited, he found a “desolate wasteland” where, just weeks earlier, had stood “a slaughterhouse the like of which the human race has not known from the age of primitive barbarism to these cruel days of ours.”

Being a thoroughly indoctrinated communist who despised fascism with all his soul, Grossman couldn’t resist making generalizations about the entire German people. It would have been impossible not to, given the passions of the time, and the millions upon millions who had already died in the Soviet Union because of Nazism:

The thrift, precision, calculation and pedantic cleanliness common to many Germans are not bad traits in themselves. Applied to agriculture or to industry they produce laudable results. Hitlerism applied these traits to crime against mankind and the Reich’s SS behaved in the Polish labor camp exactly as though they were raising cauliflower or potatoes.

To read Grossman’s report today is to be shocked and numbed by the horrors and reminded that so many human beings are capable of unimaginable atrocity – if encouraged, if made to feel virtuous in their killing, if made to believe they kill for a greater cause. Grossman mentions a character called “Sviderski, the one-eyed German from Odessa, known as the “hammer expert” because of his consummate skill at killing without firearms. Within the space of a few minutes, he hammered to death fifteen children between the ages of eight and thirteen, declared unfit for work.”

Those taken to the gas chambers had to be fooled before they could be killed. The victims at Treblinka “were told that they were being taken to the Ukraine for farm work, and were permitted to take twenty kilograms of baggage and food with them. In many cases the Germans forced their victims to purchase railway tickets to the station of Ober-Majdan, their code name for Treblinka. The code name was adopted because Treblinka soon acquired such fearful notoriety throughout Poland that it had to be dropped.”

There were no sheep. They were lied to, then murdered:

All the trains from the West-European countries were unguarded and provided with the normal sleepers and dining-cars. The passengers had large trunks and valises with them and abundant supplies of food, and when the trains stopped at stations the travelers’ children would run out to ask how far it was to Ober-Majdan. To keep up the farce at the expense of the people coming from Western Europe until the very last moment, the railhead at the death camp was modeled to look like a railway station. The platform at which each batch of twenty cars was unloaded had a regular station building with ticket offices, a baggage room, a restaurant and arrows pointing in all directions with the signs: “To Bialystok” “To Baranowicze” “To Wolkowysk”. As the trains pulled in a band of well-dressed musicians struck up a tune. A station guard in railway uniform collected the tickets from the passengers, letting them through to a large square.

This is what happens when people blindly believe in a Führer, a single man who promises to solve their problems while blaming one group for the misfortunes of an entire nation:

They were marched down a straight avenue about 120 meters long and two wide, and bordered by flowers and firs. This path led to the place of execution. Wire was stretched along either side of the path, which was lined by guards in black uniforms and SS men in gray standing shoulder to shoulder. The path was covered with white sand and as the victims marched forward with upraised arms they saw the fresh imprint of bare feet on the sand: the small footprints of women, the tiny footprints of children, the impress of heavy aged feet. These faint tracks on the sand were all that remained of the thousands of people who had recently passed down this path just as the present four thousand were passing now and as the next four thousand would pass two hours later and the thousands more waiting there on the railway track in the woods…The Germans called it “‘the road from which there is no return.”

Read Grossman’s almost forensic account of Treblinka here -https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/essays/grossmantreblinka46.pdfthe – for the stomach-turning details of how ordinary Germans and Ukrainians perfected industrial murder and, indeed, delighted in it. I have only so much space here. What I feel obliged to quote in full is Grossman’s declaration about the role of the writer, the reporter:

It is the duty of a writer to tell the truth however grueling, and the duty of the reader to learn the truth. To turn aside, or to close one’s eyes to the truth is to insult the memory of the dead. The person who does not learn the whole truth will never understand what kind of enemy, what sort of monster, our army is waging battle against to the death.

The men and women of the SS were human. They were not an aberration, “robots who mechanically carried out the wishes of others”:

They were profoundly and sincerely convinced that they were doing the correct and necessary thing. They explained in detail the superiority of their race over all other races; they delivered tirades about German blood, the German character and the German mission... Their conscience never worried them for the simple reason that they had no conscience. They went in for physical exercises, took great care of their health, drank milk every morning, were extremely fussy about their personal comforts, planted flowers in front of their homes and built summerhouses. Several times a year they went home to Germany on leave since their particular “profession” was considered “injurious” and their superiors jealously guarded their health.

In July 1944, Vassily Grossman witnessed racism in its most extreme form. When people today ask why their parents did not talk about the “war” or share their heroic deeds, we need look no further than Grossman’s report on Treblinka for a partial answer: they wanted to forget, even if they could not.

Grossman could not forget, even if he wanted to. Amid the ashes and rubble of Treblinka, Grossman stared at humankind at its worst:

We walk over the bottomless Treblinka earth and suddenly something causes us to halt in our tracks. It is the sight of a lock of hair gleaming like burnished copper, the soft lovely hair of a young girl trampled into the ground, and next to it a lock of light blonde hair, and farther on a thick dark braid gleaming against the light sand; and beyond that more and more. These are evidently the contents of one, but only one, of the sacks of hair the Germans had neglected to ship off...The last wild hope that it might be a ghastly nightmare has gone. The lupine pods pop open, the tiny peas beat a faint tattoo as though a myriad of tiny bells were really ringing a funeral dirge deep down under the ground. And it seems the heart must surely burst under the weight of sorrow, grief and pain that is beyond human endurance.

Let’s give Grossman one last passage:

Wars like the present are terrible indeed. Rivers of innocent blood have been spilled by the Germans. But today it is not enough to speak of the responsibility of Germany for what has happened. Today we must speak of the responsibility of all nations and of every citizen in the world for the future…We must remember that racism, fascism will emerge from this war not only with bitter recollections of defeat but also with sweet memories of the ease with which it is possible to slaughter millions of defenseless people. This must be solemnly borne in mind by all who value honor, liberty and the life of all nations of all mankind.

Grossman returned to Moscow in August 1944 and collapsed from nervous exhaustion, taking to his bed. It had all been too much, too harrowing. Thankfully, he had managed to produce one of the greatest pieces of reporting in history, let alone from WWII.

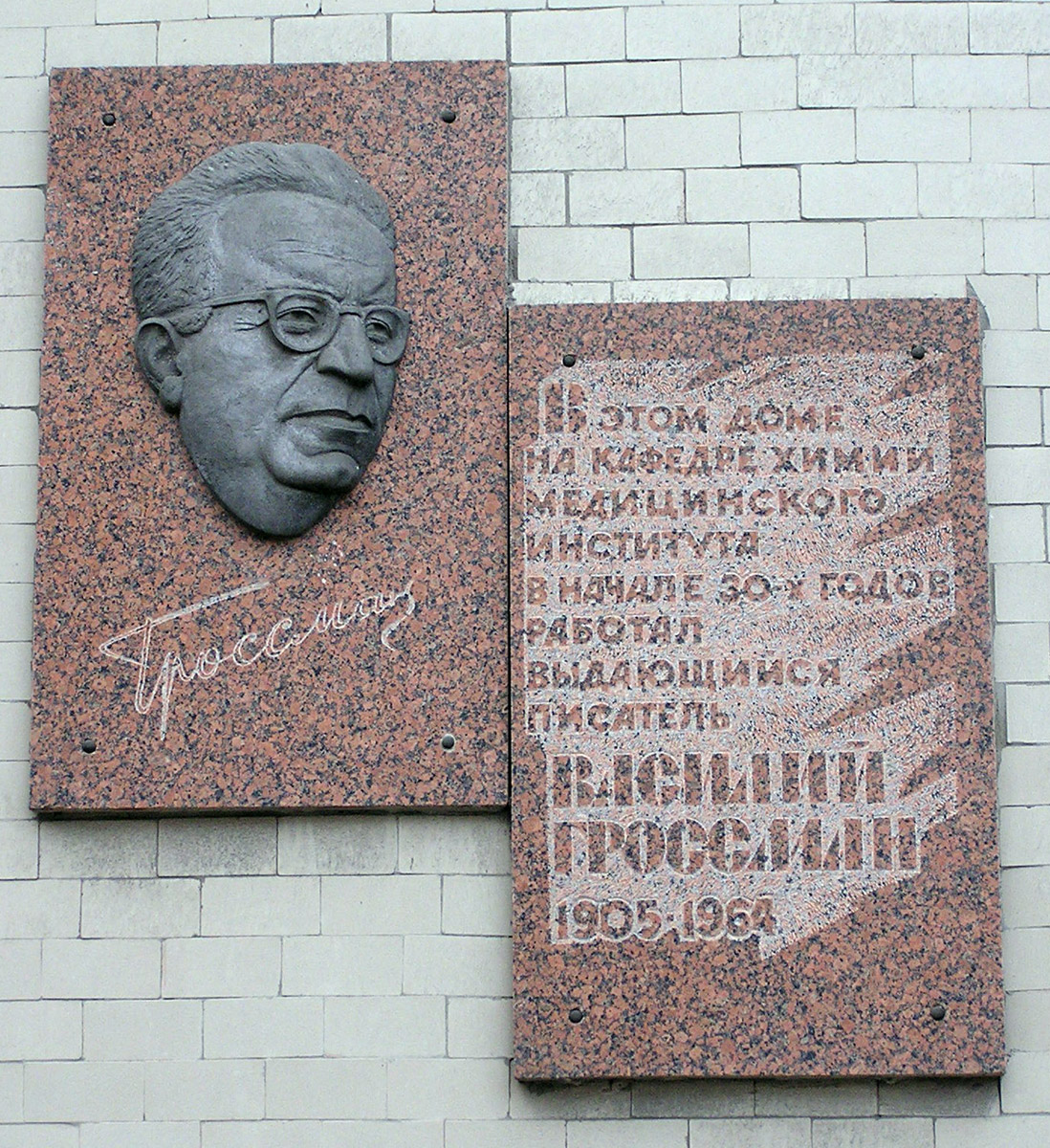

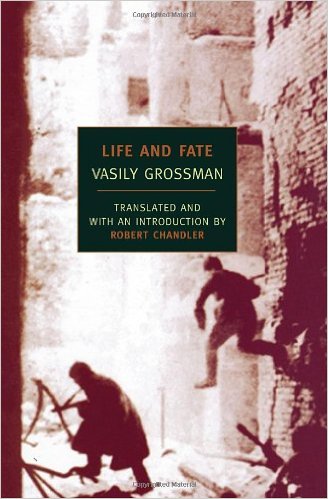

After the war, Grossman helped compile the Black Book, a documentation of the Holocaust. It was suppressed by the Soviet state and this led to profound disillusionment with the system whose military he had so ably championed as a journalist. Ironically, perhaps, he finally fell afoul of what had always been, at its core, an anti-human, utterly repressive form of government. His masterpiece, “Life and Fate,” one of the great 20th-century novels, was not permitted to be published. Grossman died in 1964 of stomach cancer, aged 58. It was not until 1988, during glasnost, that this epic appeared in print in the Soviet Union, which was soon to fall apart.