World War II brought to the fore many talented cartoonists. Here are my favorites.

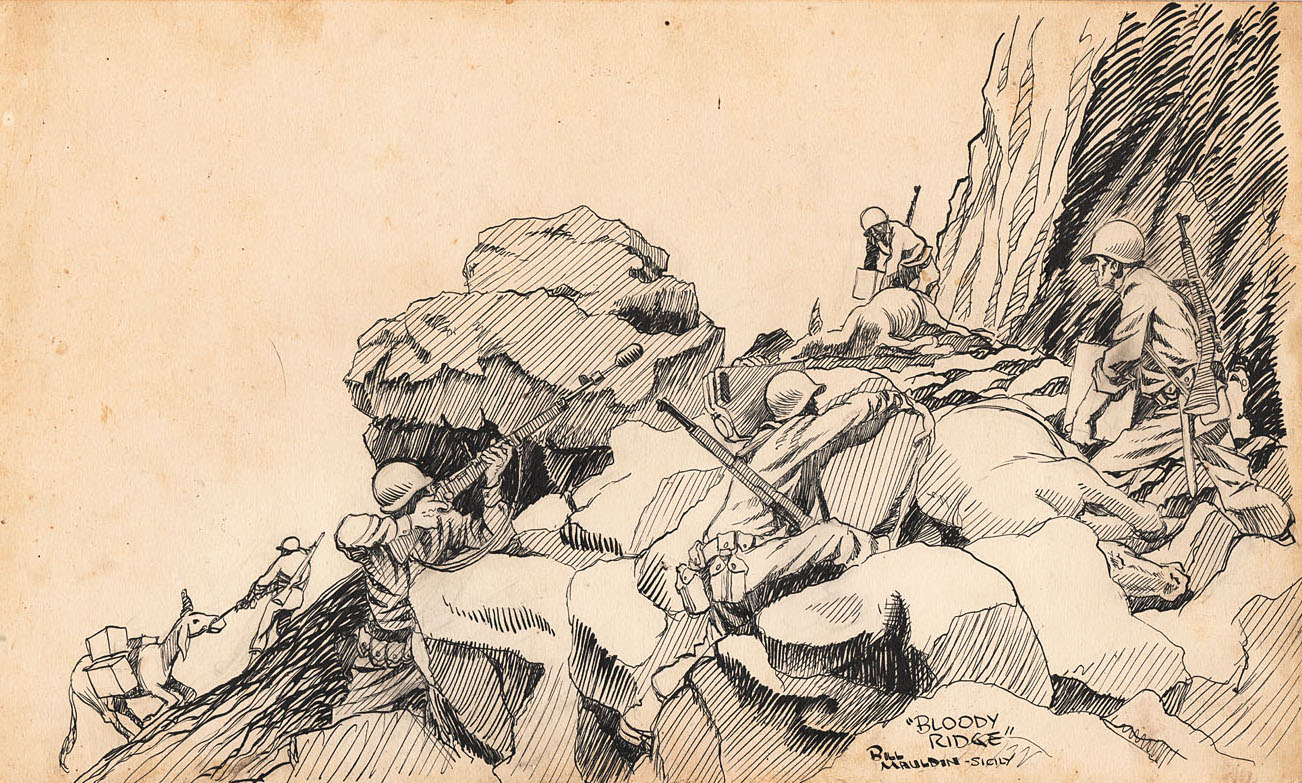

1] Bill Mauldin

A wiry, cocky high school dropout from New Mexico, Mauldin joined the Arizona National Guard in 1940 and ended up serving with the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. Mauldin first saw action in Sicily in 1943, where he got a part-time cartoonist job for the “45th Division News.” He followed the Allies through Italy, a land of mountains, mules, and mud, and switched to Stars and Stripes, wrote a wonderful, hugely popular book, Up Front, one of my all-time favorites, and finished the war as the youngest-ever winner of the Pulitzer Prize.

Mauldin’s most famous cartoons featured the bearded, cynical, worn-out Willie and Joe. Although he famously ran afoul of General George S. Patton, who despised his treasonous portrayal of GIs, he was protected by generals like Theodore Roosevelt Jr., and Lucian Truscott, who told Mauldin that if he received no complaints, he wasn’t doing any good. The troops loved the black humor and gritty reality in Mauldin’s work – it showed the dirt, grime, boredom, waste, and pointlessness of so much of front-line life, and made him a household name for the rest of his career.

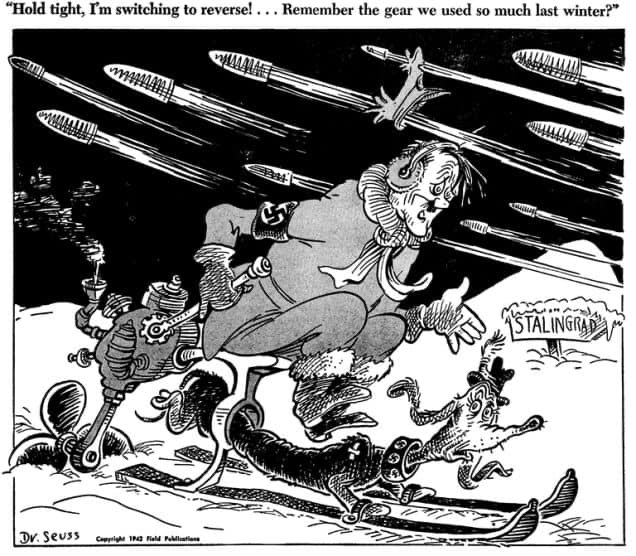

2] Dr. Seuss

Before he became a worldwide phenomenon, selling over 600 million books in his lifetime, “Dr. Seuss," aka Theodor Seuss Geisel, was a highly successful illustrator working in advertising. When the war broke out, he turned to political cartoons, drawing more than 400 in two years for a left-wing New York daily newspaper, PM, before working for the Treasury Department, War Production Board, and United States Army Air Forces. He targeted isolationists such as Charles Lindbergh and was a strong supporter of President Roosevelt. Of course, Hitler and Mussolini were easy to caricature, but Dr. Seuss’s cartoons of them were especially impressive, depicting both dictators as evil buffoons while rallying support to defeat them.

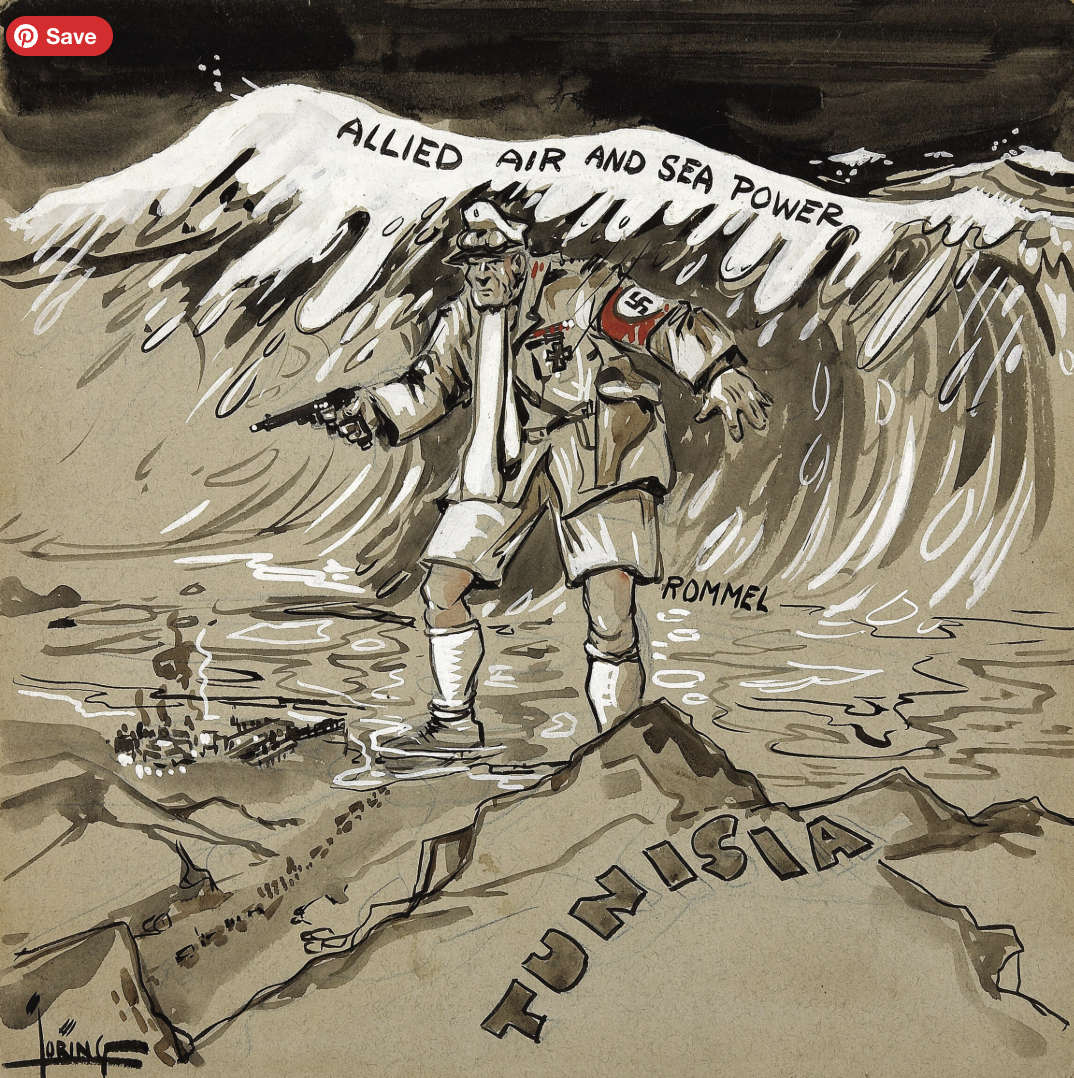

3] Paule Loring

Loring grew up in Rhode Island, known for its surprisingly long shoreline, and became a talented painter, exceptionally skilled at seascapes, before taking odd jobs and finally landing in the offices of the Providence Journal-Bulletin. The cartoon above, featuring a stunning breaking wave, is titled “In an Unenviable Position.” It depicts German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, affectionately known as “The Desert Fox” by the British, after they defeated him, which first occurred in North Africa in 1942. In reality, Rommel’s defeat was more due to Hitler’s stubbornness, specifically his refusal to let German troops retreat, than to Rommel’s own shortcomings. Loring returned to painting after the war and passed away in 1968 in his native Rhode Island, a place he loved.

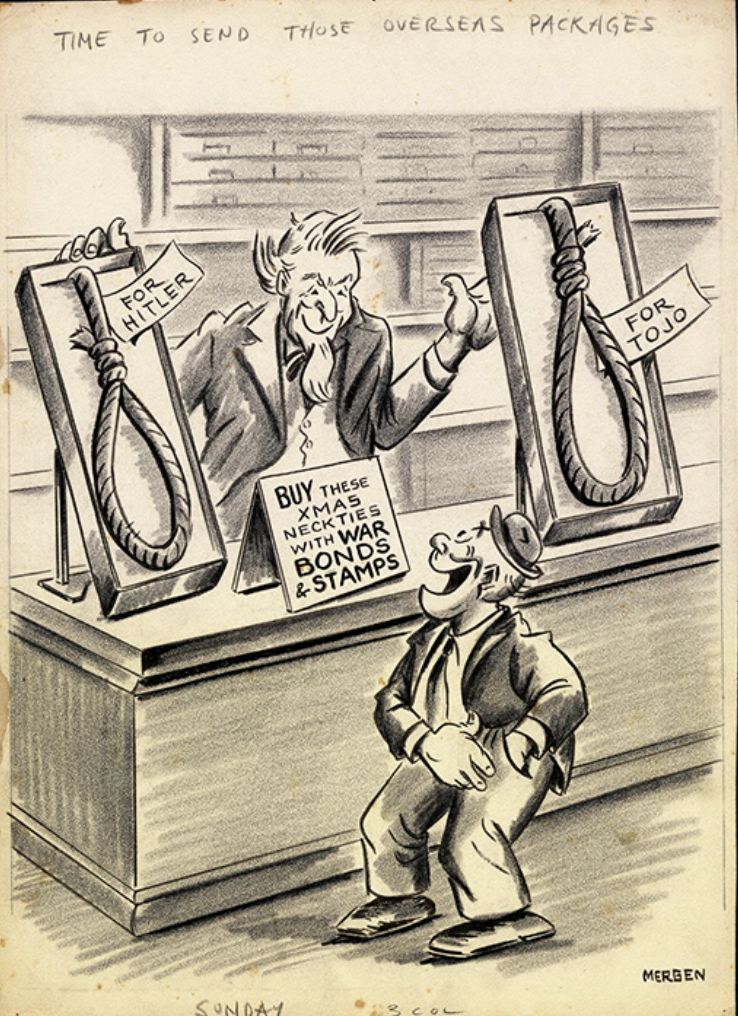

4] Anne Mergen

Mergen was a true pioneer. Born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1906, she became a commercial artist in Chicago before moving to Miami and starting work in fashion advertising. The Miami Daily News recognized her talent when she submitted fashion illustrations. Her first editorial cartoon was published in April 1933. Three years later, she became a full-time editorial cartoonist, serving as the only female political cartoonist in the U.S. for nearly thirty years.

The cartoon above was titled “Time to Send Those Overseas Packages” and appeared on September 26, 1943. It’s a powerful, impactful call to action. Buying war bonds would result in Hitler and Tojo being hanged by Uncle Sam. Mergen died in 1994, having created over 7000 cartoons.

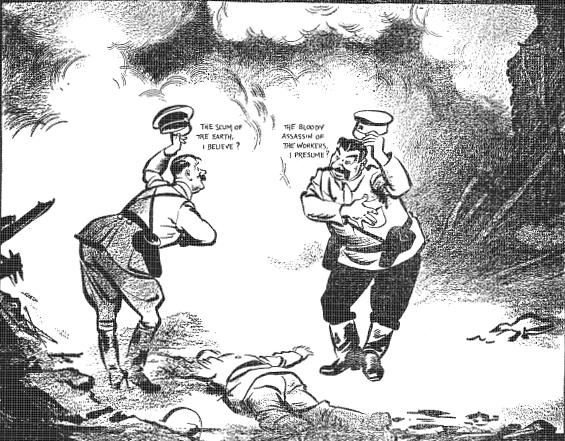

5] David Low.

Low, born in New Zealand, was once called “the greatest caricaturist in the world.” After moving to the UK, he became the leading cartoonist for the right-wing Evening Standard, insisting on no political interference because of his center-left views. He despised appeasers and relentlessly mocked Europe’s new strongmen.

In 1937, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, as detestable a Nazi as one could imagine, with his club foot and endless hatreds, told British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax that British political cartoons, especially Low's, were harming Anglo-German relations. If only Low’s cartoons had been published in Germany and Italy, perhaps many fascists might have learned to smile at themselves; instead, they were utterly, tediously humorless, though very easy to mock with their pathetic pomp and fancy dress.

Before their planned invasion of Britain in 1940, the Nazis compiled the Black Book, listing Britons Hitler aimed to arrest. You can buy a copy today from the Imperial War Museum. I recently reviewed it and realized that every notable artist, writer, and decent person I admire from that era was on the list. Low was also included. If the RAF fighters pilots hadn’t succeeded during the Battle of Britain in summer 1940, the entire intelligentsia could have been eradicated, and comic geniuses like Low might have been forced to scrawl their last words on torture chamber walls before execution at some brutal British Dachau, with the Tower of London handed over to the Gestapo.

The British upper classes have always produced top-tier traitors, especially those educated at Cambridge. Many posh Brits were all too eager to fly a swastika if it meant defeating the communist masses and avoiding combat in the trenches. Low was criticized by many as a “war monger,” just like Churchill. However, unlike Churchill, Low was neither an imperialist nor a war monger, but a highly talented cartoonist. His long career ultimately led him to my alma mater, The Guardian, which is now grimly woke, but was not so when Low contributed to its pages. He was knighted in 1962 and died the following year. Even the establishment ultimately loved him.

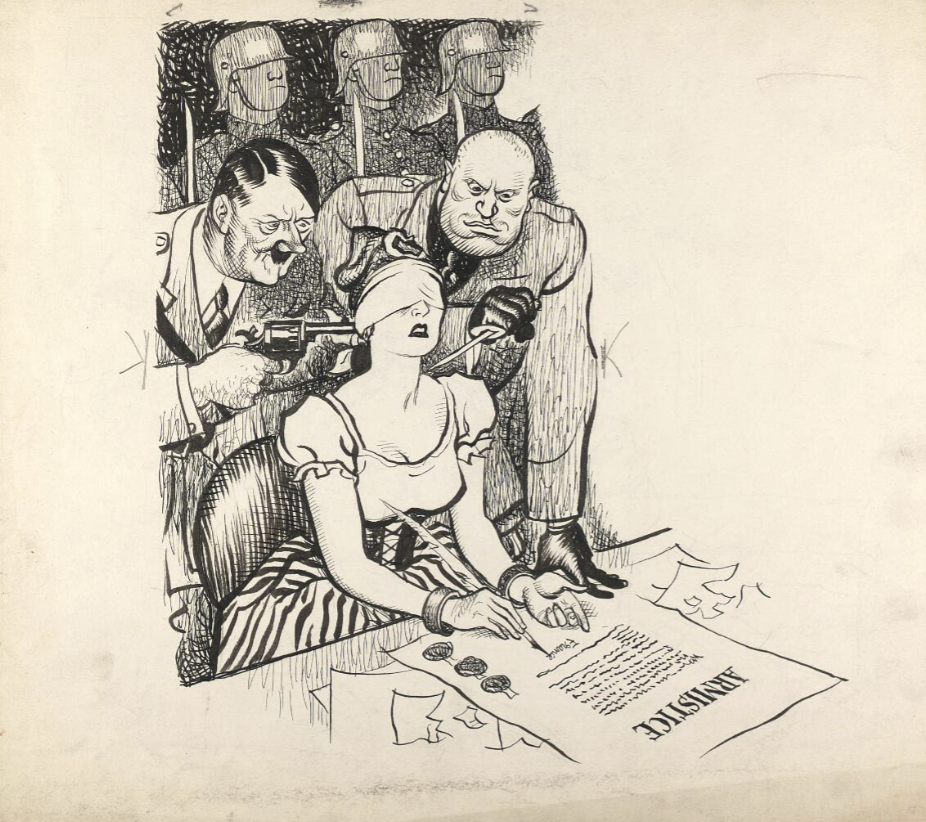

6] Leslie Illingworth

Leslie Gilbert Illingworth, born in Barry, Wales, in 1902, studied at Cardiff Art School before earning a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London. He then returned to Cardiff as a cartoonist. In 1939, he joined the popular Daily Mail, creating hilarious cartoons that boosted Britain's morale during WWII. Despite being Welsh, he was unusually fond of Churchill, who had famously suppressed miners’ strikes in the Welsh valleys early in his career. After the war, he shifted his focus to domestic issues but still drew about international matters. He became Chief Cartoonist at Punch in 1945, a significant achievement, and continued working for the Daily Mail, making a splash and earning a good living, until his retirement in 1969. He died ten years later.

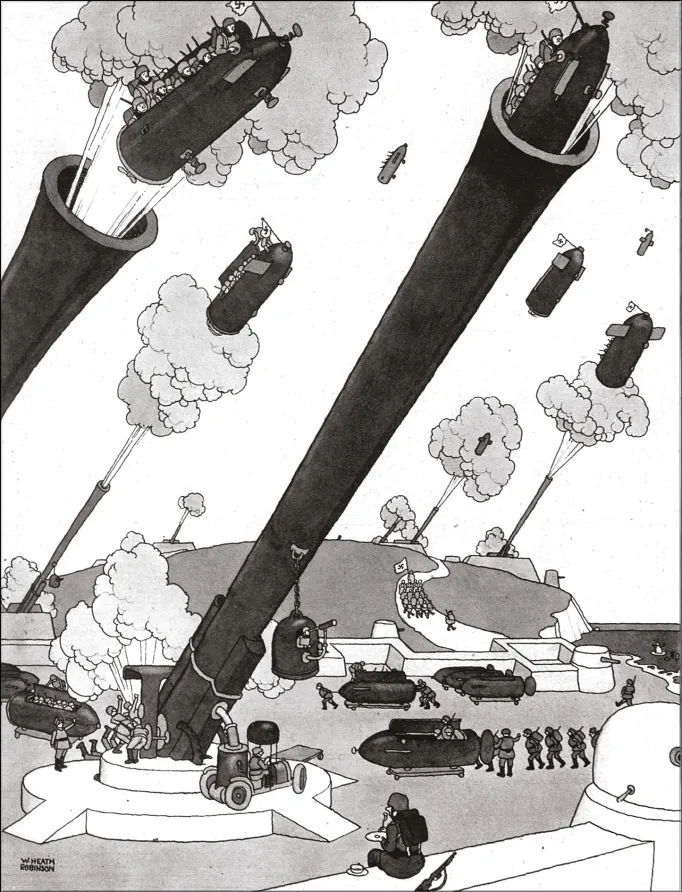

7] Heath Robinson

William Heath Robinson was too old to enlist in WWI, having been born in 1872. He was one of the most extraordinarily brilliant eccentrics in British art history and remains one of the most beloved illustrators who ever lived. Few who have grown up in England in the last century are unable to recognize his pictures. To this day, Heath Robinson is adored for his genius—his most extraordinary talent was depicting whimsically elaborate machines that accomplished simple tasks. These were fantastic, humorous inventions, and they featured in some of his last work during WWII.

Heath Robinson died in the fall of 1944, before victory, but by then he was so admired that one of the “automatic analysis machines” built at Bletchley Park to break German codes was named “Heath Robinson.” Eat your heart out Bill Gates and Steve Jobs—having a machine named after you that helped win WWII surely takes the cake. The “Heath Robinson” machine was the father of the “Colossus”, otherwise known as “the world's first programmable digital electronic computer.”

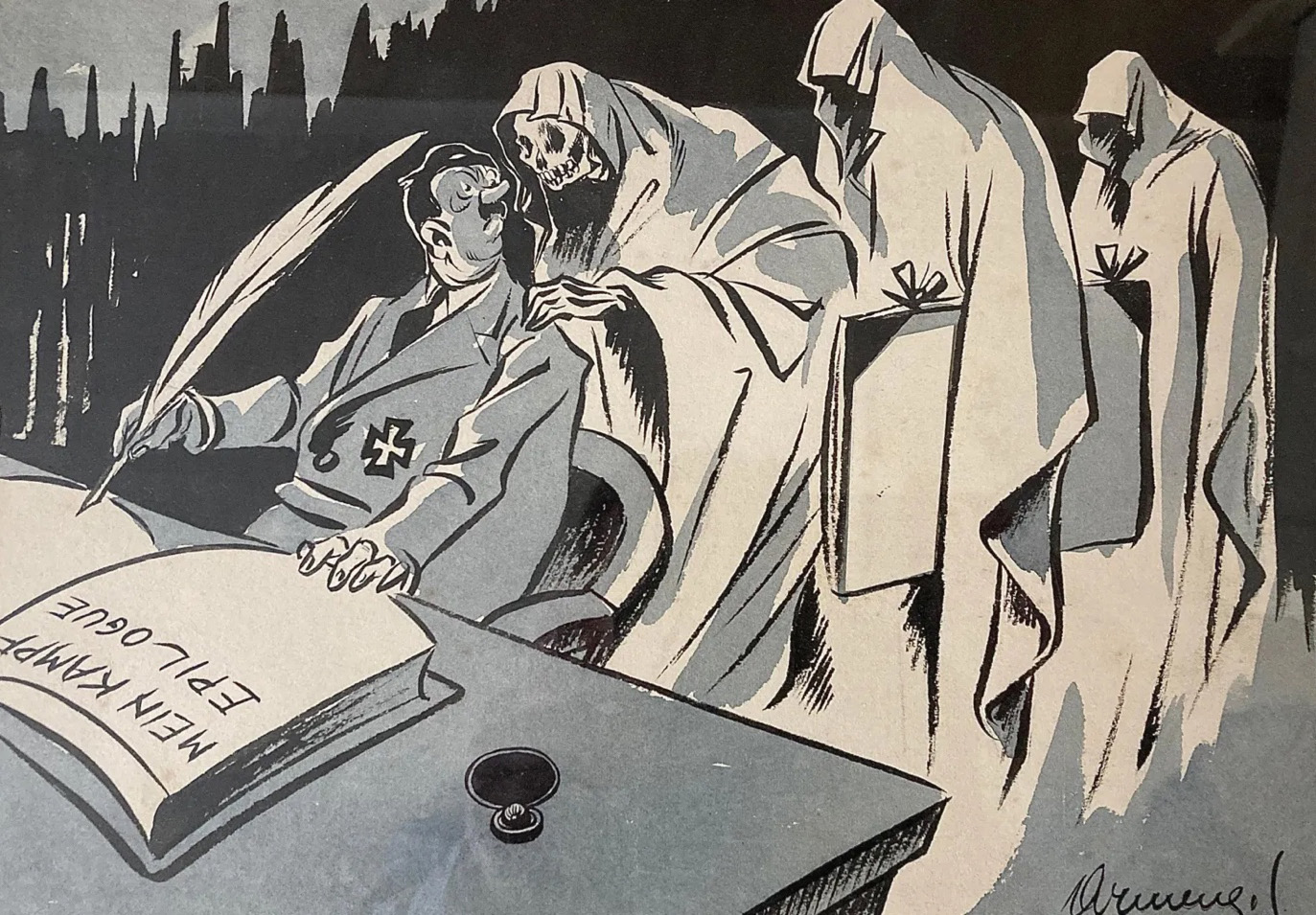

8] Mario Armegnol

Armengol detested fascism and fought against it with a gun, a pencil, and a paintbrush. He was a refugee from fascism, thriving worldwide once again today, after fleeing his native Spain, where Franco had murdered his fellow Republicans with the help of Hitler and Mussolini. After serving in the French Foreign Legion, he arrived in Glasgow, Britain, in July 1940, where he gained permission to stay. Suffering from “shell shock,” now known as post-traumatic stress disorder, he had been evacuated with French forces from Narvik during the disastrous Norway Campaign.

He moved from London to the quiet village of Laneham, where he started creating cartoons for the British Ministry of Information. “The good citizens of Laneham, a tiny village,” it has been reported, “were basically farmers and they'd never seen a foreign person before, let alone a man with a strong accent, wearing a beret, who was sending these large parcels on a weekly basis through their tiny post office to His Majesty's government, so they thought he must be a spy.”

Ultimately, he created about 2,000 cartoons and artworks to support propaganda efforts. They are some of the finest cartoons of the war—beautiful and haunting. After the war, he worked for ICI and designed posters for British Rail before passing away in 1995.

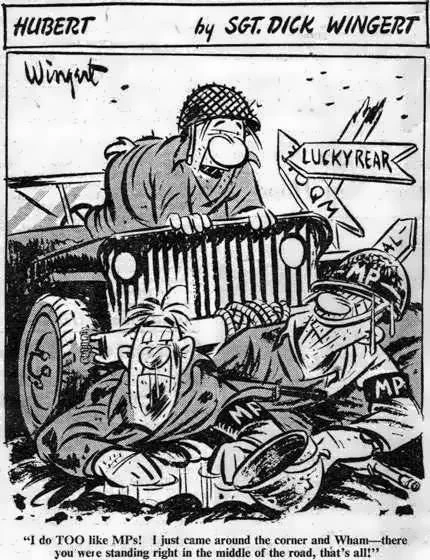

9] Richard Wingert

Born in Iowa the year after WWI ended, Richard Wingert was perhaps lucky to have a father who disliked artists and wanted him to become a businessman – the stubborn Wingert naturally rebelled, and thankfully, he became one of WWII’s most beloved and popular cartoonists.

Wingert was drafted into the Army in February 1941. He sent samples of his work to Stars and Stripes, and his work impressed the editors so much that he was transferred to London, where he created the character “Hubert” — a plump, accident-prone GI with an endless supply of dry one-liners. “The army is a wonderful place for a cartoonist to start,” Wingert later said. “There is no end of material, and all you have to do is make a humorous comment on how you personally feel about any given situation of army life, and you have a million other guys who feel the same way you do.”

10] Charles Alston

The US recruited the best when it mattered most. The Office of War Information hired black artist Alston to create “motivational” drawings, primarily aimed at African American newspapers during the war. His delicate, clever images depicted celebrated “colored” warriors and conveyed essential messages to readers. Some black newspapers were hesitant about entering World War II. Indeed, it was thought that dying for others’ freedom abroad was a bit of a reach when fellow Americans were still practically enslaved by segregation and Jim Crow laws at home. The Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, was even investigated for treason and sedition because of its “Double V” campaign, promoting black dual victories— in the U.S. and on the battlefield. Alston’s art made everyone proud and demonstrated that Black Americans, in combat and at home, were just as patriotic as their white counterparts.